GUEST BLOG, By Ryan Lamb, Editor, West Coaster magazine--Lucky San Diego homebrewers have a hops farm within easy driving distance, where you can visit and pick your own fresh hops. Called Hopportunity Farm, the location is nearby to the rustic old mining town, Julian, California.

Getting there is part of the fun, but pay attention to the directions above and be sure to call or email farmer "hopalong" Phil Warren to let him know you're coming before you trek up into the mountains. prwarren46@gmail.com or 1-858-735-2977.

Source: www.westcoastersd.com

Multilectual Daily Online Magazine focusing on World Architecture, Travel, Photography, Interior Design, Vintage and Contemporary Fiction, Political cartoons, Craft Beer, All things Espresso, International coffee/ cafe's, occasional centrist politics and San Diego's Historic North Park by award-winning journalist Tom Shess

Total Pageviews

Friday, July 31, 2020

SPACE CADETS / COMET NEOWISE IS VISIBLE THIS WEEK

Check out comet Neowise in the evening sky this week. It is the brightest comet in 23 years as seen across the world. Next trip by Earth will be in 7,000 years—that’s 9020 for those of you counting.

BTW the photo above was grabbed off the Internet and sent to us without a byline. We do know the photo was taken in the Cuyamaca Mountains in East San Diego County. And, it makes a helluva nice screen saver image.

Thursday, July 30, 2020

BREAKING NEWS / NASA’S COVERAGE OF MARS 2020 LAUNCH UP UP AND AWAY

NASA's Mars 2020 Perseverance rover mission is on its way to the Red Planet to search for signs of ancient life and collect samples to send back to Earth

A United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket with NASA’s Mars 2020 Perseverance rover onboard launches from Space Launch Complex 41, Thursday, July 30, 2020, at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. The Perseverance rover is part of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, a long-term effort of robotic exploration of the Red Planet.

Photo Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky

SPACE CADETS / GODSPEED NASA’S MARS ROVER PERSEVERANCE

|

| The target for Perseverance is Jezero Crater, where signs of a watery past are even clearer, when viewed from orbit, than those at Gale Crater. |

Today, Mars is hostile to life. It's too cold for water to stay liquid on the surface, and the thin atmosphere lets through high levels of radiation, potentially sterilising the upper part of the soil.

But it wasn't always like this. Some 3.5 billion years ago or more, water was flowing on the surface. It carved channels still visible today and pooled in impact craters. A thicker carbon dioxide (CO2) atmosphere would have blocked more of the harmful radiation.

Water is a common ingredient in biology, so it seems plausible that ancient Mars once offered a foothold for life.

In the 1970s, the Viking missions carried an experiment to look for present-day microbes in the Martian soil. But the results were judged inconclusive.

|

| Previous missions have found evidence that Mars had the right ingredients for life billions of years ago |

The Curiosity rover, which touched down in 2012, found the lake that once filled its landing site at Gale Crater could have supported life. It also detected organic (carbon-containing) molecules that serve as life's building blocks.

Now, the Perseverance rover will explore a similar environment with instruments designed to test for the signatures of biology.

"I would say it's the first Nasa mission since Viking to do that," said Ken Williford, the mission's deputy project scientist, from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

"Viking was the search for extant life - that is, life that might be living on Mars today. Whereas the more recent Nasa approach has been to explore ancient environments because the data we have suggest that the earliest history of the planet tells us that Mars was most habitable during its first billion years."

The target for Perseverance is Jezero Crater, where signs of a watery past are even clearer, when viewed from orbit, than those at Gale Crater.

The rover will drill into Martian rocks, extracting cores that are about the size of a piece of chalk. These will be sealed away - cached - in containers and left on the surface. These will be collected by another rover, sent at a later date, blasted into Mars orbit and delivered to Earth for analysis. It's all part of a collaboration with the European Space Agency (Esa) called Mars Sample Return.

But the rover will also perform plenty of science on the surface.

Jezero features one of the best-preserved Martian examples of a delta: layered structures formed when rivers enter open bodies of water and deposit rocks, sand and - potentially - organic carbon.

"There's a river channel flowing in from the west, penetrating the crater rim; and then just inside the crater, at the river mouth, there's this beautiful delta fan that's exposed. Our plan is to land right in front of that delta and start exploring," said Dr Williford.

Media captionDrive with Nasa's next Mars rover through Jezero Crater

The delta contains sand grains originating from rocks further upstream, including a watershed to the north-west.

"The cement between the grains is very interesting - that records the history of the water interacting with that sand at the time of the delta deposition in the lake," says Ken Williford.

"It provides potential habitats for any organisms living between those grains of sand. Bits of organic matter from any organisms upstream could potentially be washed in."

Jezero is located in a region that has long been of interest to science. It's on the western shoulder of a giant impact basin called Isidis, which shows the strongest Martian signals of the minerals olivine and carbonate as measured from space. "Carbonate minerals are one of the key targets that led us to explore this region," says Ken Williford.

|

| Stromatolites in Shark Bay, Australia |

Terrestrial carbonates can lock up biological evidence within their crystals. One type of structure that sometimes survives is a stromatolite.

These are formed when many millimetre-scale layers of bacteria and sediment build up over time into larger structures, sometimes with domed shapes. On Earth, they occur along ancient shorelines, where sunlight and water are plentiful.

Billions of years ago, Jezero's shore was exactly the kind of place where stromatolites could have formed - and have been preserved.

Perseverance will examine the carbonate-rich bathtub ring with its science instruments, to see whether structures like this ever formed there.

|

| The layers in a stromatolite are irregular and wrinkly. Perseverance will look for similar shapes |

Within this data-set, scientists will "look for concentrations of biologically important elements, minerals and molecules - including organic matter. In particular, [it's] when those things are concentrated in shapes that are potentially suggestive of biology", says Ken Williford.

Drawing together many lines of evidence is vital; visual identifications alone won't be enough to convince scientists of a biological origin, given the high bar for claims of extra-terrestrial life. Short of a huge surprise, finds are likely to be described only as potential biosignatures until rocks are sent to Earth for analysis.

Referring to stromatolites, Dr Williford explains: "The layers tend to be irregular and wrinkly, as you might expect for a bunch of microbes living on top of each other. That whole thing can fossilise in a way that's visible even to the cameras.

"But it's when we see shapes like that and, maybe, one layer has a different chemistry than the next, but there is some repeating pattern, or we see organic matter concentrated in specific layers - those are the ultimate biosignatures that we might hope to find."

Yet, Mars might not give up its secrets easily. In 2019, scientists from the mission visited Australia to familiarise themselves with fossil stromatolites that formed 3.48 billion years ago in the country's Pilbara region.

"We will have to look harder [on Mars] than when we went to the Pilbara... our knowledge of their location comes from many decades of many geologists going year-after-year and mapping the territory," says Ken Williford.

On Mars, he says, "we are the first ones".

Dr. Briony Horgan and colleagues have been working at Lake Salda, Turkey, where carbonate beaches and terraces can be found. The area's rocks are similar in composition to what's seen at Jezero Crater

But what if the rover doesn't see anything as large and obvious as a stromatolite?

On Earth, we can detect fossilised microbes at the level of individual cells. But in order to see them, scientists have to cut out a slice of rock, grind it to within the thickness of a sheet of paper and study it on a glass slide.

No rover can do this. But, then, it might not have to.

"It's very rare to find an individual microbe hanging out on its own," says Dr Williford.

"Back when they were alive - if they were anything like Earth microbes - they would have joined together in little communities that build up into structures or clumps of cells that are detectable to the rover."

After exploring the crater floor, scientists want to drive the rover up onto the rim. Rock cores taken here, when analysed on Earth, could provide an age for the impact that carved out the crater and a maximum age for the lake.

But there's another reason for being interested in the crater rim. When a large space object slams into rocks containing water, the huge energy can set up hydrothermal systems - where hot water circulates through the rocks. The hot water dissolves minerals from the rocks that provide the necessary ingredients for life.

|

| Jezero's delta here we come |

The current mission scenario foresees the rover driving to the nearby north-east Syrtis region as an "aspirational goal".

It's more ancient even than Jezero and also holds the promise of exposed carbonates - which may have formed in a different way to those in the crater.

If, by the end of this mission, signs of past life haven't presented themselves, the search won't be over. The focus will turn to those cores, waiting for delivery to Earth.

But the exciting prospect remains that the mission might not just throw up more questions, but answers too. That outcome could be planet-shaking. Whatever lies in wait for plucky Perseverance, we are on the verge of a new phase in our understanding of Earth's near-neighbour.

Wednesday, July 29, 2020

THE WORLD: TRAVEL / HONG KONG, A DAY IN THE LIFE OF ONE OF THE BEST CITIES ANYWHERE

|

| Hong Kong Harbor as viewed from the top of Victoria Peak |

BEGIN YOUR ONE DAY TOUR.

7:00 Early morning is the best time to visit Victoria Peak, the highest point on Hong Kong Island, with its dazzling panoramas of the city, Victoria Harbor and the sprawl of China beyond. Catch the first Peak Tram, which leaves at 7am from Garden Road. The 130-year-old funicular climbs almost vertically on its eight-minute journey, slicing through the skyscrapers and allowing voyeuristic glimpses into apartments along the way. At the top head for Lugard Road and walk the 3.5-kilometre Peak Circle Walk for mind-blowing 360 degrees views.

09:00 Jump in a taxi (red Toyota taxis are cheap and plentiful) and ask for the IFC, one of the city’s glitziest malls. Grab coffee from Fuel, Hong Kong’s best caffeine hit, before heading to the basement bus station: we’re taking the deliciously scenic 260 route to Stanley. The road winds along the south of the island with sandy beaches on one side and emerald subtropical forest on the other (more than 40 per cent of Hong Kong is National Park). Stroll around charming Stanley village, famous for its market, or relax on St. Stephen’s beach.

11:00 Head back to IFC in a taxi: it’s time to experience the joys of the world’s longest covered escalator. The 800-meter Mid-Levels Escalator climbs right through the city’s heart. You’ll coast by a riot of neon-brightened streets, past tiny shops and cafes so close you can almost touch them. Regular exit and entry points provide plenty of opportunity to hop off and explore.

11:30 Hop off the escalator at Hollywood Road to see modern design fuse spectacularly with old temples. Visit the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, a brilliant renovation of the colonial Central Police Station and prison that hosts performances and artworks inside 16 heritage buildings and two striking aluminium-clad boxes. A little further along Hollywood Road, find one of the city’s oldest temples, Man Mo, built in 1847 and a tribute to the gods of literature (Man) and war (Mo). As red and gold swirl before your eyes, huge coils of incense smoulder from the ceiling and a fortune-teller will divine your fate in English.

13:00 Walk your way past antique dealers back down to Central (an easy 20 minutes) for the city’s best dim sum at the divine China Club. Formed by the late businessman and socialite Sir David Tang, this restaurant in the ex-Bank of China building is all old-Shanghai glamour with an opulent sweeping staircase, Chinese art and lacquered rosewood dining chairs. Technically, this is a members’ club but the concierge at a good hotel will usually be able to sweet-talk you into a reservation. Order the xiao long bao (broth-filled steamed pork dumplings), Peking duck and char siu bao (barbecue pork buns).

14:30 After lunch, take a 15-minute walk to the harbour and pier number 7 to ride the historic Star Ferry. The iconic green and white ferries have been shuttling across Victoria Harbour for more than 130 years and the $2.70 fare is an absolute bargain for the stunning trip to Tsim Sha Tsui on Kowloon. The take on Hong Kong Island from the middle of the harbour is simply breath-stopping.

15:00 When you disembark in Kowloon, it’s just a quick taxi ride to the Jade Market on Battery Street in the bustling Jordan neighbourhood. At this undercover mecca for souvenir-hunters, stalls hawk jewellery, Buddha statues, amulets and any sort of trinket you could imagine would be made from the emerald stone believed to promote wisdom and peace. Bring your polite haggling skills – it’s all part of the fun.

16:00 A quick taxi ride will bring you to historic Peninsula Hotel and a world of oriental elegance. The acclaimed afternoon tea is served in the gracious colonial Lobby (all potted palms, gilded columns and swathes of marble) and guests feast on dainty finger sandwiches and pastries to the sound of a string quartet. Make the occasion extra special by taking the 15-minute Fly and Tea helicopter flight from the hotel’s rooftop helipad before teatime.

18:00 First nip back to your hotel for a quick brush up. Then head to the seriously upscale Terrace bar at Sevva on the top floor of the Princes Building. In a city with a rich pedigree in swanky rooftop bars, this is the best in town. A magical wraparound balcony with comfy sofas and candlelit tables provides dazzling views over the city, harbour and the Norman Foster-designed HSBC building. Order the guava martini and marvel at the shining city as the night lights twinkle to life.

20:00 Take the Mid-Levels Escalator up to hip Gough Street in SoHo to discover one of the most happening restaurants in the city. Gough’s on Gough is owned by furniture designer Timothy Oulton and serves up stylish interiors with a menu that fuses elemental Asian purism and international influences with modern British cooking. Classic seafood and meat dishes get a sexy spin.

Tuesday, July 28, 2020

SPACE CADETS / SAMOA TO SPACE

Christina Koch, NASA astronaut, who has participated in International Space Station duty (expeditions 59, 60, 61) is the most recent female astronaut to return to Earth. Her 328 days in microgravity set the record for the longest time in space for a woman during a single mission. During that time, she worked on hundreds of experiments, including studies of protein crystals and plants in space.

She participated in a number of studies to support future exploration missions, including research into how the human body adjusts to weightlessness, isolation, radiation and the stress of long-duration spaceflight. Koch earned bachelor’s degrees in electrical engineering and physics and a master’s degree in electrical engineering from North Carolina State University in Raleigh, NC, and worked at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s Laboratory for High Energy Astrophysics, contributing to scientific instruments on several missions studying cosmology and astrophysics.

Koch served as station chief of the American Samoa Observatory and has contributed to the development of instruments used to study radiation particles for the Juno mission and the Van Allen Probe.

Cupola Observational Module

The cupola is a small module designed for the observation of operations outside the station such as robotic activities, the approach of vehicles, and spacewalks. Its six side windows and a direct nadir viewing window provide spectacular views of Earth and celestial objects. The windows are equipped with shutters to protect them from contamination and collisions with orbital debris or micrometeorites. The cupola house the robotic workstation that controls the Canadarm2.

Height: 4.7 feet

Diameter: 9.8 feet

Mass: 4,136 pounds

Monday, July 27, 2020

RULE, BRITANNIA / HER MAJESTY'S POCKETBOOK / 2018-19

How is the work of The Queen funded? How much does the Royal Family cost the tax payer each year? Does The Queen pay tax – and if not, why not? And do the Crown Jewels and Royal Palaces belong to The Queen?

The Monarchy has sometimes been described as an expensive institution, with Royal finances shrouded in confusion and secrecy. In reality, the Royal Household is committed to ensuring that public money is spent as wisely and efficiently as possible, and to making Royal finances as transparent and comprehensible as possible.

Each year the Royal Household publishes a summary of Head of State expenditure, together with a full report on Royal public finances. These reports can be downloaded from the Media Centre. Click here.

This section provides an outline of how the work of the Monarchy is funded. It includes information on Head of State expenditure, together with information about other aspects of Royal finances.

On 1 April 2012 the arrangements for the funding of The Queen’s Official Duties changed. The new system of funding, referred to as the ‘Sovereign Grant’, replaces the Civil List and the three Grants-in-Aid (for Royal Travel, Communications and Information, and the Maintenance of the Royal Palaces) with a single, consolidated annual grant.

On 1 April 2012 the arrangements for the funding of The Queen’s Official Duties changed. The new system of funding, referred to as the ‘Sovereign Grant’, replaces the Civil List and the three Grants-in-Aid (for Royal Travel, Communications and Information, and the Maintenance of the Royal Palaces) with a single, consolidated annual grant.

The Sovereign Grant is designed to be a more permanent arrangement than the old Civil List system, which was reign-specific. Funding for the Sovereign Grant comes from a percentage of the profits of the Crown Estate revenue (initially set at 15%). The grant will be reviewed every five years by the Royal Trustees (the Prime Minister, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Keeper of the Privy Purse), and annual financial accounts will continue to be prepared and published by the Keeper of the Privy Purse.

The new system provides for the Royal Household to be subject to the same audit scrutiny as other government expenditure, via the National Audit Office and the Public Accounts Committee.

If you would like to find out more, please visit the Treasury’s website CLICK HERE.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the government’s chief financial minister and as such is responsible for raising revenue through taxation or borrowing and for controlling public spending. He has overall responsibility for the work of the Treasury.

AMERICAN CONNECTION

Rishi, 39, went to Winchester College and studied Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford University. He was also a Fulbright Scholar at Stanford University (USA) where he studied for his MBA.

RETRO FILES / HEMINGWAY REVISITS WHERE HE WAS BLOWN UP AND WISHES HE HADN’T

Earlier posting in Pillar to Post omitted photos--Our apologies.

From the public domain via The Library of America: from Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises & Other Writings 1918 -1926. First published in the Toronto Daily Star, July 22, 1922.

From Library of America:

That fall, Hemingway was working as a reporter for the Kansas City Star—a job his father secured for him in lieu of military service. At the paper, he met and interviewed Theodore Brumback, who had just returned from a five-month stint as an ambulance driver in northern France and whose story presented Hemingway with a possible path to the war. Brumback ended up writing a riveting account of his service, and its appearance in the Star in February coincided with the American Red Cross call for volunteers in Italy. Soon thereafter, both young men enlisted with the Ambulance Corps, went to New York for two weeks of training, and reached Milan in early June. They separated shortly after their arrival when the Red Cross sent Hemingway to Schio, a town 150 miles to the east.

|

| Hemingway at the American Red Cross Hospital, Milan, 1918 |

A Veteran Visits the Old Front--Wishes He Had Stayed Away

By Ernest Hemingway, Summer 1922.

Don’t go back to visit the old front. If you have pictures in your head of something that happened in the night in the mud at Paschendaele or of the first wave working up the slope of Vimy, do not try and go back to verify them. It is no good. The front is as different from the way it used to be as your highly respectable shin, with a thin, white scar on it now, is from the leg that you sat and twisted a tourniquet around while the blood soaked your puttee and trickled into your boot, so that when you got up you limped with a “squidge” on your way to the dressing station.

|

| Ernest Hemingway in the uniform of the Royal Army of Italy, 1918, age 18 |

Not only is it battlefields that have changed in quality and feeling and gone back into a green smugness with the shell holes filled up, the trenches filled in, the pillboxes blasted out and smoothed over and the wire all rolled up and rotting in a great heap somewhere. That was to be expected, and it was in- evitable that the feelings in the battlefields would change when the dead that made them both holy and real were dug up and reburied in big, orderly cemeteries miles away from where they died. Towns where you were billeted, towns unscarred by war, are the ones where the changes hit you hardest. For there are many little towns that you love, and after all, no one but a staff officer could love a battlefield.

There may be towns back of the old Canadian front, towns with queer Flemish names and narrow, cobbled streets, that have kept their magic. There may be such towns. I have just come from Schio, though. Schio was the finest town I remember in the war, and I wouldn’t have recognized it now — and I would give a lot not to have gone.

Schio was one of the finest places on earth. It was a little town in the Trentino under the shoulder of the Alps, and it contained all the good cheer, amusement and relaxation a man could desire. When we used to be in billets there, everyone was perfectly contented and we were always talking about what a wonderful place Schio would be to come and live after the war. I particularly recall a first- class hotel called the Due Spadi, where the food was superb and we used to call the factory where we were billeted the “Schio Country Club.”

|

| E.H. recovering (on his 19th birthday) in hospital from mortar shell fragments in his leg and machine gun wounds in his knee and foot. |

“The town is changed since the war,” I said to the girl, she was red-cheeked and black-haired and discontented-looking, who sat on a stool, knitting behind the zinc- covered bar.

“Yes?” she said without missing a stitch.

“I was here during the war,” I ventured.

“So were many others,” she said under her breath, bitterly. “Grazie, Signor,” she said with mechanical, insolent courtesy as I paid for the drink and went out.

That was Schio. There was more, the way the Due Spadi had shrunk to a small inn, the factory where we used to be bil- leted now was humming, with our old entrance bricked up and a flow of black muck polluting the stream where we used to swim. All the kick had gone out of things. Early next morning I left in the rain after a bad night’s sleep.

There was a garden in Schio with the wall matted with wisteria where we used to drink beer on hot nights with a bombing moon making all sorts of shadows from the big plane tree that spread above the table. After my walk in the afternoon I knew enough not to try and find that garden. Maybe there never was a garden.

|

| Modern day Schio, Italy in the Northwest region |

It was the same old road that some of the same old brigades marched along through the dust of June of 1918, being rushed to the Piave to stop another offensive. Their best men were dead on the rocky Carso, in the fighting around Goritzia, on Mount San Gabrielle, on Grappa and in all the places where men died that nobody ever heard about. In 1918 they didn’t march with the ardor that they did in 1916, some of the troops strung out so badly that, after the battalion was just a dust cloud way up the road, you would see poor old boys hoofing it along the side of the road to ease their bad feet, sweating along under their packs and rifles and the deadly Italian sun in a long, horrible, never-ending stagger after the battalion.

So we went down to Mestre, that was one of the great railheads for the Piave, traveling first class with an assorted carriageful of evil-smelling Italian profiteers going to Venice for vacations. In Mestre, we hired a motorcar to drive out to the Piave and leaned back in the rear seat and studied the map and the country along the long road that is built through the poisonous green Adriatic marshes that flank all the coast near Venice.

|

| E.H. awarded Italy's Silver Medal of Military Valor |

Then a wind blew the mist away from the Adriatic and we saw Venice way off across the swamp and the sea standing gray and yellow like a fairy city.

Finally the driver wiped the last of the grease off his hands into his over- luxuriant hair, the gears took hold when he let the clutch in and we went off along the road through the swampy plain.

Fossalta, our objective, as I remembered it, was a shelled-to-pieces town that even rats couldn’t live in. It had been within trench-mortar range of the Austrian lines for a year and in quiet times the Austrian had blown up anything in it that looked as though it ought to be blown up. During active sessions it had been one of the first footholds the Austrian had gained on the Venice side of the Piave, and one of the last places he was driven out of and hunted down in and very many men had died in its rubble-and debris-strewn streets and been smoked out of its cellars with flammenwerfers during the house-to-house work.

|

| What's left of the bridge over the Piave River, 1918 |

I climbed the grassy slope and above the sunken road where the dugouts had been to look at the Piave and looked down an even slope to the blue river. The Piave is as blue as the Danube is brown. Across the river were two new houses where the two rubble heaps had been just inside the Austrian lines.

|

| Italian Trenches, WWII, near Venice and the Piave River, Summer, 1918 |

On our way back to the motorcar we talked about how jolly it is that Fossalta is all built up now and how fine it must be for all the families to have their homes back. We said how proud we were of the way the Italians had kept their mouths shut and rebuilt their devastated districts while some other nations were using their destroyed towns as showplaces and reparation ap- peals. We said all the things of that sort that as decent-thinking people we thought — and then we stopped talking. There was nothing more to say. It was so very sad.

For a reconstructed town is much sadder than a devastated town. The people haven’t their homes back. They have new homes. The home they played in as children, the room where they made love with the lamp turned down, the hearth where they sat, the church they were married in, the room where their child died, these rooms are gone. A shattered village in the war always had a dignity, as though it had died for something. It had died for something and something better was to come. It was all part of the great sacrifice. Now there is just the new, ugly futility of it all. Everything is just as it was — except a little worse.

So we walked along the street where I saw my very good friend killed, past the ugly houses toward the motorcar, whose owner would never have had a motorcar if it had not been for the war, and it all seemed a very bad business. I had tried to re-create something for my wife and had failed utterly. The past was as dead as a busted Victrola record. Chasing yesterdays is a bum show — and if you have to prove it, go back to your old front.

Saturday, July 25, 2020

AMERICANA / BASEBALL IS BACK JUST IN TIME FOR POLITICAL CARTOONISTS

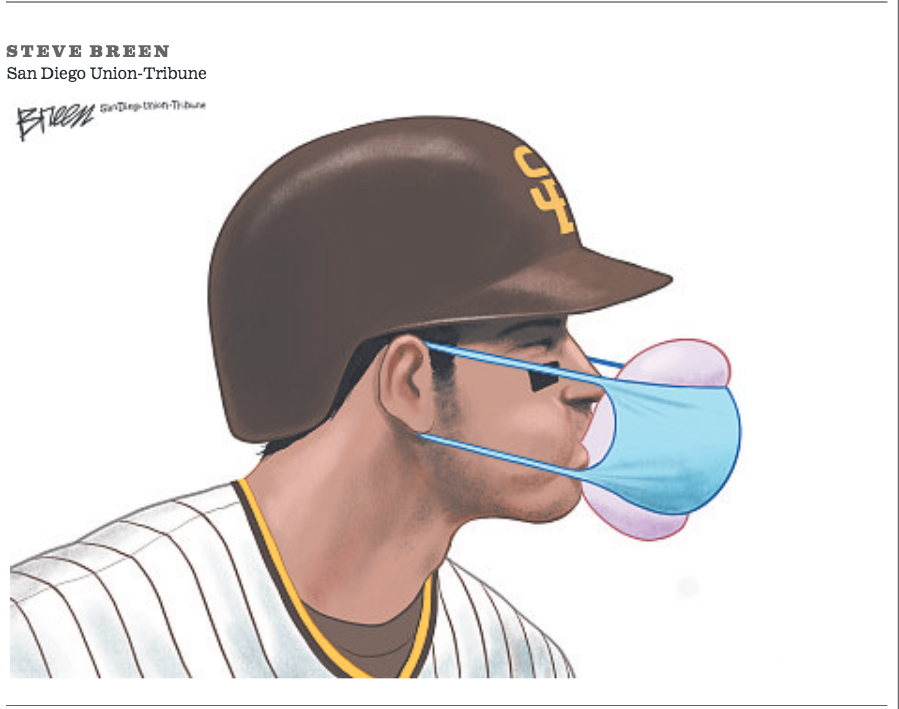

|

| Steve Breen of the San Diego Union-Tribune captures the dilemma of masked men playing the national pastime. Other political cartoonists took aim at the various rules changes for the 60 game season. |

|

| By Bob Englehart via CagleCartoons.com |

|

| Then--there's this... |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)