Multilectual Daily Online Magazine focusing on World Architecture, Travel, Photography, Interior Design, Vintage and Contemporary Fiction, Political cartoons, Craft Beer, All things Espresso, International coffee/ cafe's, occasional centrist politics and San Diego's Historic North Park by award-winning journalist Tom Shess

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, February 28, 2023

Monday, February 27, 2023

AMERICANA / EVER WONDER HOW MANY GUN DEATHS OCCUR IN US ON ANY GIVEN YEAR (SINCE 2013?

The Gun Violence Archive [GVA] was established in Fall of 2013 as an independent research and data collection organization to provide comprehensive data for the national conversation regarding gun violence. GVA worked with several groups which collected statistics of the 2013 toll of deaths by gun violence.

When GVA consolidated these projects in late 2013, the mission was expanded to also document the tens of thousands of gun related injuries and other gun crime. The overall goal of GVA is to provide the best, most detailed, accessible data on the subject to add clarity to the ongoing discussion on gun violence, gun rights, and gun regulations.

GVAs mission is not confined to the debate on gun rights vs gun regulations, it is equally focused on understanding crime at a street level, providing crime statistics broken down to the Congressional District, State legislator district level.

GVA will continue to research the best methods of providing unbiased, unfiltered data on gun violence in America. To that end, we will, by necessity alter methodology if need arises and announce those changes here.

GVA overall goal, however will not change, providing the most comprehensive, verifiable data on the subject of gun violence without bias. The raw numbers, and their underlying information are tools for researchers to interpret.

SOURCE: Gun Violence Archive 1133 Connecticut Avenue Washington DC 20036 inquiry@gva.us.com or @gundeaths

Sunday, February 26, 2023

ROAD TRIP / CLASSIC SWISS HIWAYS, TUNNELS IN WINTER WEATHER.

As of December 23, 2022

• Auto route should not be confused with the Gotthard Base Tunnel which was completed in 2016. The GBT is the longest railway tunnel in the world to date. Now back to Route A-2 for autos, trucks and buses.

Euro tour the North/South Gotthard Pass, the A-2 highway route of older Swiss freeways and roads and dozens of tunnels mostly in rainy weather; good image from front of a DiniK truck. Saint-Gotthard Automobile Tunnel (German Gotthard-Strassentunnel, Ital. Galleria stradale del San Gottardo is a tunnel in the Lepontine Alps (Switzerland) with a length of 16.9 km (10.5 miles).

The height of the northern portal is 1080 m, the southern one is 1146 m above sea level. It connects 2 Swiss cantons: Uri in the north and Ticino in the south.

PART 1 [skipped]

SAME TRIP BUT DURING SUNNY WEATHER CLICK HERE.

Saturday, February 25, 2023

COFFEE BEANS & BEINGS / A CUP WITH GERTRUDE STEIN, 1922

“Coffee is real good when you drink it gives you time to think. It’s a lot more than just a drink; it’s something happening. Not as in hip, but like an event, a place to be, but not like a location, but like somewhere within yourself. It gives you time, but not actual hours or minutes, but a chance to be, like be yourself, and have a second cup.” --Gertrude Stein.

Author, poet, social critic and patron of the arts, Gertrude Stein, right, and her life’s companion Alice B. Toklas [photo above] are seated in 1922 inside their art filled apartment in Paris. Note the coffee cup and saucer on the table with perhaps a sherry nearby. The apartment was located at 27 rue de Fleurus, where the ex-pat Americain lived for 35 years.

In the photo (below) taken in May 1930, one will note that Stein or Toklas or both had rearranged the décor, especially the artwork. Pablo Picasso’s portrait of Stein is in the upper right of the image.

Friday, February 24, 2023

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE PERFECT NAP

|

| Aim for a 30 minute cat nap for max benefits |

How to avoid waking from a nap feeling groggy and grumpy

GUEST BLOG / By Jessica Stillman, Reporter, INC.com--Naps, study after study tells us, are great for your memory, cognitive function, physical health, and all-around productivity.

Research is equally clear that naps boost the performance of employees (and busy entrepreneurs).

So why, when you take one, do you often wake up feeling logy and listless?

If all the scientists are right, and naps are so great for you, why do they often leave so many of us feeling bad?

The answer to this question might surprise you -- taking a good nap is harder than it first appears. That's counterintuitive as we've all been napping successfully since the day we were born. What could be less complicated than rolling out a mat on the floor or your kindergarten classroom and snuggling in?

But while it's true that napping comes naturally to humans, experts insist that getting a refreshing nap as a busy adult requires a basic understanding of one essential principle -- the 30-90 rule.

It's all about our sleep cycles.

I was reminded of this fact recently when I came across an article from our sister site, Fast Company, with a fun premise: What can truckers, who often have to snatch whatever shuteye they can at odd hours, teach us about how to get better sleep? The whole article is worth a read, but one tidbit from Dean Croke, a freight industry insider who teaches sleep science classes to truckers and shift workers, stood out.

Croke explains to writer Stephanie Vozza that human sleep isn't one monolithic experience. When we doze off, our brains cycle through different sleep phases in regular blocks of about 90 minutes. "If we were to wire our brains with scalp electrodes, like they do in sleep studies, you would see different electrical pulses between the neurons in the brain," Croke says.

"They translate to different levels of sleep." For about the first 30 minutes after lying down, you're likely in a phase of light sleep. Eventually you enter a phase of deeper sleep which lasts between 30 and 75 minutes. Finally, before waking, you experience a period of REM sleep where you do your most intense dreaming.

Each phase has different functions, Croke tells Vozza. "Deep sleep deals with the fatigue.

REM sleep deals with memory and mood, archiving the memories and flushing out the brain of the things it doesn't need," he says. That's not just fascinating biological trivia.

Knowledge of sleep cycles can also help you plan a nap that leaves you refreshed and clearheaded rather than groggy and grumpy.

The key, according to Croke, is to avoid trying to wake up from deep sleep. This means you should probably aim to sleep for 30 minutes or less, or give yourself at least 90 minutes -- a.k.a. the 30-90 rule.

NASA agrees with the truckers. Croke comes at this rule from an unusual background, but he's far from the only expert who insists that naps should either be short or long and nothing in between.

NASA, for instance, tested the ideal nap length to boost cognitive performance and found a snooze of 26 minutes was ideal, boosting performance on the job by 34 percent. That's an oddly precise finding but it basically boils down to the 30 in the 30-90 rule.

If your aim is to refresh your brain and boost memory and concentration, a short nap is best. If you need to whittle away at a more serious sleep debt because you haven't been getting the recommended seven to eight hours a night, then science agrees with Croke that you should aim to complete a full sleep cycle.

As one Boston Globe summary of the science of sleep puts it: "Naps of 90 to 120 minutes usually comprise all stages, including REM and deep slow-wave sleep, which helps to clear your mind, improve memory recall, and recoup lost sleep."

As an added bonus, waking from REM sleep leaves you feeling much perkier than trying to drag yourself out of deep sleep. So, if you find yourself dragging after your afternoon snoozes, the problem is probably not your nap, but your nap technique. For better results, heed the science and always set your alarm for either 30 minutes or less, or 90 minutes or more.

Thursday, February 23, 2023

RETRO FILES / MYTHS OF AMERICAN REVOLUTION AND ESPECIALLY THAT OF GEORGE WASHINGTON AS A MILITARY STRATEGIST

|

| King George III and Lord North British leaders made a miscalculation when they assumed that resistance from the colonies, as the Earl of Dartmouth predicted, could not be "very formidable." |

A noted historian debunks the conventional wisdom about America’s War of Independence

GUEST BLOG / By John Ferling, an excerpt in Smithsonian Magazine from his book “The Ascent of George Washington: The hidden political (not military) genius of an American icon. Illustration by Joe Ciardiello.

We think we know the Revolutionary War. After all, the American Revolution and the war that accompanied it not only determined the nation we would become but also continue to define who we are. The Declaration of Independence, the Midnight Ride, Valley Forge—the whole glorious chronicle of the colonists’ rebellion against tyranny is in the American DNA. Often it is the Revolution that is a child’s first encounter with history.

Yet much of what we know is not entirely true. Perhaps more than any defining moment in American history, the War of Independence is swathed in beliefs not borne out by the facts. Here, in order to form a more perfect understanding, the most significant myths of the Revolutionary War are reassessed.

MYTH #I. Great Britain Did Not Know What It Was Getting Into

In the course of England’s long and unsuccessful attempt to crush the American Revolution, the myth arose that its government, under Prime Minister Frederick, Lord North, had acted in haste. Accusations circulating at the time—later to become conventional wisdom—held that the nation’s political leaders had failed to comprehend the gravity of the challenge.

Actually, the British cabinet, made up of nearly a score of ministers, first considered resorting to military might as early as January 1774, when word of the Boston Tea Party reached London. (Recall that on December 16, 1773, protesters had boarded British vessels in Boston Harbor and destroyed cargoes of tea, rather than pay a tax imposed by Parliament.) Contrary to popular belief both then and now, Lord North’s government did not respond impulsively to the news. Throughout early 1774, the prime minister and his cabinet engaged in lengthy debate on whether coercive actions would lead to war. A second question was considered as well: Could Britain win such a war?

By March 1774, North’s government had opted for punitive measures that fell short of declaring war. Parliament enacted the Coercive Acts—or Intolerable Acts, as Americans called them—and applied the legislation to Massachusetts alone, to punish the colony for its provocative act. Britain’s principal action was to close Boston Harbor until the tea had been paid for. England also installed Gen. Thomas Gage, commander of the British Army in America, as governor of the colony. Politicians in London chose to heed the counsel of Gage, who opined that the colonists would “be lyons whilst we are lambs but if we take the resolute part they will be very meek.”

Britain, of course, miscalculated hugely. In September 1774, colonists convened the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia; the members voted to embargo British commerce until all British taxes and the Coercive Acts were repealed. News of that vote reached London in December. A second round of deliberations within North’s ministry ensued for nearly six weeks.

Throughout its deliberations, North’s government agreed on one point: the Americans would pose little challenge in the event of war. The Americans had neither a standing army nor a navy; few among them were experienced officers. Britain possessed a professional army and the world’s greatest navy. Furthermore, the colonists had virtually no history of cooperating with one another, even in the face of danger. In addition, many in the cabinet were swayed by disparaging assessments of American soldiers leveled by British officers in earlier wars. For instance, during the French and Indian War (1754-63), Brig. Gen. James Wolfe had described America’s soldiers as “cowardly dogs.” Henry Ellis, the royal governor of Georgia, nearly simultaneously asserted that the colonists were a “poor species of fighting men” given to “a want of bravery.”

Questions, questions, questions.

Still, as debate continued, skeptics—especially within Britain’s army and navy—raised troubling questions. Could the Royal Navy blockade the 1,000-mile-long American coast? Couldn’t two million free colonists muster a force of 100,000 or so citizen-soldiers, nearly four times the size of Britain’s army in 1775? Might not an American army of this size replace its losses more easily than Britain? Was it possible to supply an army operating 3,000 miles from home? Could Britain subdue a rebellion across 13 colonies in an area some six times the size of England? Could the British Army operate deep in America’s interior, far from coastal supply bases? Would a protracted war bankrupt Britain? Would France and Spain, England’s age-old enemies, aid American rebels? Was Britain risking starting a broader war?

After the Continental Congress convened, King George III told his ministers that “blows must decide” whether the Americans “submit or triumph.”

North’s government agreed. To back down, the ministers believed, would be to lose the colonies. Confident of Britain’s overwhelming military superiority and hopeful that colonial resistance would collapse after one or two humiliating defeats, they chose war. The Earl of Dartmouth, who was the American Secretary, ordered General Gage to use “a vigorous Exertion of...Force” to crush the rebellion in Massachusetts. Resistance from the Bay Colony, Dartmouth added, “cannot be very formidable.”

Myth #2. Americans Of All Stripes Took Up Arms Out Of Patriotism

The term “spirit of ‘76” refers to the colonists’ patriotic zeal and has always seemed synonymous with the idea that every able-bodied male colonist resolutely served, and suffered, throughout the eight-year war.

To be sure, the initial rally to arms was impressive. When the British Army marched out of Boston on April 19, 1775, messengers on horseback, including Boston silversmith Paul Revere, fanned out across New England to raise the alarm. Summoned by the feverish pealing of church bells, militiamen from countless hamlets hurried toward Concord, Massachusetts, where the British regulars planned to destroy a rebel arsenal. Thousands of militiamen arrived in time to fight; 89 men from 23 towns in Massachusetts were killed or wounded on that first day of war, April 19, 1775. By the next morning, Massachusetts had 12 regiments in the field. Connecticut soon mobilized a force of 6,000, one-quarter of its military-age men. Within a week, 16,000 men from the four New England colonies formed a siege army outside British-occupied Boston. In June, the Continental Congress took over the New England army, creating a national force, the Continental Army. Thereafter, men throughout America took up arms. It seemed to the British regulars that every able-bodied American male had become a soldier.But as the colonists discovered how difficult and dangerous military service could be, enthusiasm waned. Many men preferred to remain home, in the safety of what Gen. George Washington described as their “Chimney Corner.” Early in the war, Washington wrote that he despaired of “compleating the army by Voluntary Inlistments.” Mindful that volunteers had rushed to enlist when hostilities began, Washington predicted that “after the first emotions are over,” those who were willing to serve from a belief in the “goodness of the cause” would amount to little more than “a drop in the Ocean.” He was correct. As 1776 progressed, many colonies were compelled to entice soldiers with offers of cash bounties, clothing, blankets and extended furloughs or enlistments shorter than the one-year term of service established by Congress.

The following year, when Congress mandated that men who enlisted must sign on for three years or the duration of the conflict, whichever came first, offers of cash and land bounties became an absolute necessity. The states and the army also turned to slick-tongued recruiters to round up volunteers. General Washington had urged conscription, stating that “the Government must have recourse to coercive measures.” In April 1777, Congress recommended a draft to the states. By the end of 1778, most states were conscripting men when Congress’ voluntary enlistment quotas were not met.

Moreover, beginning in 1778, the New England states, and eventually all Northern states, enlisted African-Americans, a practice that Congress had initially forbidden. Ultimately, some 5,000 blacks bore arms for the United States, approximately 5 percent of the total number of men who served in the Continental Army. The African-American soldiers made an important contribution to America’s ultimate victory. In 1781, Baron Ludwig von Closen, a veteran officer in the French Army, remarked that the “best [regiment] under arms” in the Continental Army was one in which 75 percent of the soldiers were African-Americans.

Longer enlistments radically changed the composition of the Army. Washington’s troops in 1775-76 had represented a cross-section of the free male population. But few who owned farms were willing to serve for the duration, fearing loss of their property if years passed without producing revenue from which to pay taxes. After 1777, the average Continental soldier was young, single, propertyless, poor and in many cases an outright pauper. In some states, such as Pennsylvania, up to one in four soldiers was an impoverished recent immigrant.

Patriotism aside, cash and land bounties offered an unprecedented chance for economic mobility for these men. Joseph Plumb Martin of Milford, Connecticut, acknowledged that he had enlisted for the money. Later, he would recollect the calculation he had made at the time: “As I must go, I might as well endeavor to get as much for my skin as I could.” For three-quarters of the war, few middle-class Americans bore arms in the Continental Army, although thousands did serve in militias.

Myth #3. Continental Soldiers Were Always Ragged And Hungry

Accounts of shoeless continental army soldiers leaving bloody footprints in the snow or going hungry in a land of abundance are all too accurate. Take, for example, the experience of Connecticut’s Private Martin. While serving with the Eighth Connecticut Continental Regiment in the autumn of 1776, Martin went for days with little more to eat than a handful of chestnuts and, at one point, a portion of roast sheep’s head, remnants of a meal prepared for those he sarcastically referred to as his “gentleman officers.”

Ebenezer Wild, a Massachusetts soldier who served at Valley Forge in the terrible winter of 1777-78, would recall that he subsisted for days on “a leg of nothing.” One of his comrades, Dr. Albigence Waldo, a Continental Army surgeon, later reported that many men survived largely on what were known as fire cakes (flour and water baked over coals). One soldier, Waldo wrote, complained that his “glutted Gutts are turned to Pasteboard.” The Army’s supply system, imperfect at best, at times broke down altogether; the result was misery and want.

But that was not always the case. So much heavy clothing arrived from France at the beginning of the winter in 1779 that Washington was compelled to locate storage facilities for his surplus.

In a long war during which American soldiers were posted from upper New York to lower Georgia, conditions faced by the troops varied widely. For instance, at the same time that Washington’s siege army at Boston in 1776 was well supplied, many American soldiers, engaged in the failed invasion of Quebec staged from Fort Ticonderoga in New York, endured near starvation.

While one soldier in seven was dying from hunger and disease at Valley Forge, young Private Martin, stationed only a few miles away in Downingtown, Pennsylvania, was assigned to patrols that foraged daily for army provisions. “We had very good provisions all winter,” he would write, adding that he had lived in “a snug room.” In the spring after Valley Forge, he encountered one of his former officers. “Where have you been this winter?” inquired the officer. “Why you are as fat as a pig.”

Myth #4. The Militia Was Useless

The nation’s first settlers adopted the British militia system, which required all able-bodied men between 16 and 60 to bear arms. Some 100,000 men served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. Probably twice that number soldiered as militiamen, for the most part defending the home front, functioning as a police force and occasionally engaging in enemy surveillance. If a militia company was summoned to active duty and sent to the front lines to augment the Continentals, it usually remained mobilized for no more than 90 days.

Some Americans emerged from the war convinced that the militia had been largely ineffective. No one did more to sully its reputation than General Washington, who insisted that a decision to “place any dependence on Militia is assuredly resting on a broken staff.”

Militiamen were older, on average, than the Continental soldiers and received only perfunctory training; few had experienced combat. Washington complained that militiamen had failed to exhibit “a brave & manly opposition” in the battles of 1776 on Long Island and in Manhattan. At Camden, South Carolina, in August 1780, militiamen panicked in the face of advancing redcoats. Throwing down their weapons and running for safety, they were responsible for one of the worst defeats of the war.

Yet in 1775, militiamen had fought with surpassing bravery along the Concord Road and at Bunker Hill. Nearly 40 percent of soldiers serving under Washington in his crucial Christmas night victory at Trenton in 1776 were militiamen. In New York state, half the American force in the vital Saratoga campaign of 1777 consisted of militiamen. They also contributed substantially to American victories at Kings Mountain, South Carolina, in 1780 and Cowpens, South Carolina, the following year.

In March 1781, Gen. Nathanael Greene adroitly deployed his militiamen in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse (fought near present-day Greensboro, North Carolina). In that engagement, he inflicted such devastating losses on the British that they gave up the fight for North Carolina. The militia had its shortcomings, to be sure, but America could not have won the war without it. As a British general, Earl Cornwallis, wryly put it in a letter in 1781, “I will not say much in praise of the militia, but the list of British officers and soldiers killed and wounded by them...proves but too fatally they are not wholly contemptible.”

Myth #5. Saratoga Was The War’s Turning Point Report

On October 17, 1777, British Gen. John Burgoyne surrendered 5,895 men to American forces outside Saratoga, New York. Those losses, combined with the 1,300 men killed, wounded and captured during the preceding five months of Burgoyne’s campaign to reach Albany in upstate New York, amounted to nearly one-quarter of those serving under the British flag in America in 1777.

|

| American general Horatio Gates accepted the surrender of British forces after the Battle of Saratoga, a major turning point in the Revolutionary War, 1777. |

But Saratoga was not the turning point of the war. Protracted conflicts—the Revolutionary War was America’s longest military engagement until Vietnam nearly 200 years later—are seldom defined by a single decisive event. In addition to Saratoga, four other key moments can be identified. The first was the combined effect of victories in the fighting along the Concord Road on April 19, 1775, and at Bunker Hill near Boston two months later, on June 17.

Many colonists had shared Lord North’s belief that American citizen-soldiers could not stand up to British regulars. But in those two engagements, fought in the first 60 days of the war, American soldiers—all militiamen—inflicted huge casualties. The British lost nearly 1,500 men in those encounters, three times the American toll. Without the psychological benefits of those battles, it is debatable whether a viable Continental Army could have been raised in that first year of war or whether public morale would have withstood the terrible defeats of 1776.

Between August and November of 1776, Washington’s army was driven from Long Island, New York City proper and the rest of Manhattan Island, with some 5,000 men killed, wounded and captured. But at Trenton in late December 1776, Washington achieved a great victory, destroying a Hessian force of nearly 1,000 men; a week later, on January 3, he defeated a British force at Princeton, New Jersey. Washington’s stunning triumphs, which revived hopes of victory and permitted recruitment in 1777, were a second turning point.

A third turning point occurred when Congress abandoned one-year enlistments and transformed the Continental Army into a standing army, made up of regulars who volunteered—or were conscripted—for long-term service. A standing army was contrary to American tradition and was viewed as unacceptable by citizens who understood that history was filled with instances of generals who had used their armies to gain dictatorial powers. Among the critics was Massachusetts’ John Adams, then a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. In 1775, he wrote that he feared a standing army would become an “armed monster” composed of the “meanest, idlest, most intemperate and worthless” men.

By autumn, 1776, Adams had changed his view, remarking that unless the length of enlistment was extended, “our inevitable destruction will be the Consequence.” At last, Washington would get the army he had wanted from the outset; its soldiers would be better trained, better disciplined and more experienced than the men who had served in 1775-76.

The campaign that unfolded in the South during 1780 and 1781 was the final turning point of the conflict. After failing to crush the rebellion in New England and the mid-Atlantic states, the British turned their attention in 1778 to the South, hoping to retake Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia.

At first the Southern Strategy, as the British termed the initiative, achieved spectacular results. Within 20 months, the redcoats had wiped out three American armies, retaken Savannah and Charleston, occupied a substantial portion of the South Carolina backcountry, and killed, wounded or captured 7,000 American soldiers, nearly equaling the British losses at Saratoga. Lord George Germain, Britain’s American Secretary after 1775, declared that the Southern victories augured a “speedy and happy termination of the American war.”

But the colonists were not broken. In mid-1780, organized partisan bands, composed largely of guerrilla fighters, struck from within South Carolina’s swamps and tangled forests to ambush redcoat supply trains and patrols. By summer’s end, the British high command acknowledged that South Carolina, a colony they had recently declared pacified, was “in an absolute state of rebellion.”

Worse was yet to come. In October 1780, rebel militia and backcountry volunteers destroyed an army of more than 1,000 Loyalists at Kings Mountain in South Carolina. After that rout, Cornwallis found it nearly impossible to persuade Loyalists to join the cause. Colonia su were not kind to the surrendering loyalists troops.

In January 1781, Cornwallis marched an army of more than 4,000 men to North Carolina, hoping to cut supply routes that sustained partisans farther south. In battles at Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse and in an exhausting pursuit of the Army under Gen. Nathanael Greene, Cornwallis lost some 1,700 men, nearly 40 percent of the troops under his command at the outset of the North Carolina campaign.

In April 1781, despairing of crushing the insurgency in the Carolinas, he took his army into Virginia, where he hoped to sever supply routes linking the upper and lower South. It was a fateful decision, as it put Cornwallis on a course that would lead that autumn to disaster at Yorktown, where he was trapped and compelled to surrender more than 8,000 men on October 19, 1781.

The next day, General Washington informed the Continental Army that “the glorious event” would send “general Joy [to] every breast” in America. Across the sea, Lord North reacted to the news as if he had “taken a ball in the breast,” reported the messenger who delivered the bad tidings.

“O God,” the prime minister exclaimed, “it is all over.”

Myth #6. General Washington Was A Brilliant Tactician And Strategist

Among the hundreds of eulogies delivered after the death of George Washington in 1799, Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College, averred that the general’s military greatness consisted principally in his “formation of extensive and masterly plans” and a “watchful seizure of every advantage.” It was the prevailing view and one that has been embraced by many historians.

In fact, Washington’s missteps revealed failings as a strategist. No one understood his limitations better than Washington himself who, on the eve of the New York campaign in 1776, confessed to Congress his “want of experience to move on a large scale” and his “limited and contracted knowledge . . . in Military Matters.”

In August 1776, the Continental Army was routed in its first test on Long Island in part because Washington failed to properly reconnoiter and he attempted to defend too large an area for the size of his army. To some extent, Washington’s nearly fatal inability to make rapid decisions resulted in the November losses of Fort Washington on Manhattan Island and Fort Lee in New Jersey, defeats that cost the colonists more than one-quarter of the army’s soldiers and precious weaponry and military stores. Washington did not take the blame for what had gone wrong. Instead, he advised Congress of his “want of confidence in the Generality of the Troops.”

In the fall of 1777, when Gen. William Howe invaded Pennsylvania, Washington committed his entire army in an attempt to prevent the loss of Philadelphia. During the Battle of Brandywine, in September, he once again froze with indecision. For nearly two hours information poured into headquarters that the British were attempting a flanking maneuver—a move that would, if successful, entrap much of the Continental Army—and Washington failed to respond. At day’s end, a British sergeant accurately perceived that Washington had “escaped a total overthrow, that must have been the consequence of an hours more daylight.”

Later, Washington was painfully slow to grasp the significance of the war in the Southern states. For the most part, he committed troops to that theater only when Congress ordered him to do so. By then, it was too late to prevent the surrender of Charleston in May 1780 and the subsequent losses among American troops in the South. Washington also failed to see the potential of a campaign against the British in Virginia in 1780 and 1781, prompting Comte de Rochambeau, commander of the French Army in America, to write despairingly that the American general “did not conceive the affair of the south to be such urgency.” Indeed, Rochambeau, who took action without Washington’s knowledge, conceived the Virginia campaign that resulted in the war’s decisive encounter, the siege of Yorktown in the autumn of 1781.

Much of the war’s decision-making was hidden from the public. Not even Congress was aware that the French, not Washington, had formulated the strategy that led to America’s triumph. During Washington’s presidency, the American pamphleteer Thomas Paine, then living in France, revealed much of what had occurred. In 1796 Paine published a “Letter to George Washington,” in which he claimed that most of General Washington’s supposed achievements were “fraudulent.” “You slept away your time in the field” after 1778, Paine charged, arguing that Gens. Horatio Gates and Greene were more responsible for America’s victory than Washington.

There was some truth to Paine’s acid comments, but his indictment failed to recognize that one can be a great military leader without being a gifted tactician or strategist. Washington’s character, judgment, industry and meticulous habits, as well as his political and diplomatic skills, set him apart from others.

In the final analysis, he was the proper choice to serve as commander of the Continental Army.

Myth #7. Great Britain Could Never Have Won The War

Once the revolutionary war was lost, some in Britain argued that it had been unwinnable. For generals and admirals who were defending their reputations, and for patriots who found it painful to acknowledge defeat, the concept of foreordained failure was alluring. Nothing could have been done, or so the argument went, to have altered the outcome. Lord North was condemned, not for having lost the war, but for having led his country into a conflict in which victory was impossible.

In reality, Britain might well have won the war. The battle for New York in 1776 gave England an excellent opportunity for a decisive victory. France had not yet allied with the Americans. Washington and most of his lieutenants were rank amateurs. Continental Army soldiers could not have been more untried. On Long Island, in New York City and in upper Manhattan, on Harlem Heights, Gen. William Howe trapped much of the American Army and might have administered a fatal blow. Cornered in the hills of Harlem, even Washington admitted that if Howe attacked, the Continental Army would be “cut off” and faced with the choice of fighting its way out “under every disadvantage” or being starved into submission. But the excessively cautious Howe was slow to act, ultimately allowing Washington to slip away.

Britain still might have prevailed in 1777. London had formulated a sound strategy that called for Howe, with his large force, which included a naval arm, to advance up the Hudson River and rendezvous at Albany with General Burgoyne, who was to invade New York from Canada. Britain’s objective was to cut New England off from the other nine states by taking the Hudson. When the rebels did engage—the thinking went—they would face a giant British pincer maneuver that would doom them to catastrophic losses. Though the operation offered the prospect of decisive victory, Howe scuttled it. Believing that Burgoyne needed no assistance and obsessed by a desire to capture Philadelphia—home of the Continental Congress—Howe opted to move against Pennsylvania instead. He took Philadelphia, but he accomplished little by his action. Meanwhile, Burgoyne suffered total defeat at Saratoga.

Most historians have maintained that Britain had no hope of victory after 1777, but that assumption constitutes another myth of this war. Twenty-four months into its Southern Strategy, Britain was close to reclaiming substantial territory within its once-vast American empire. Royal authority had been restored in Georgia, and much of South Carolina was occupied by the British.

As 1781 dawned, Washington warned that his army was “exhausted” and the citizenry “discontented.” John Adams believed that France, faced with mounting debts and having failed to win a single victory in the American theater, would not remain in the war beyond 1781. “We are in the Moment of Crisis,” he wrote. Rochambeau feared that 1781 would see the “last struggle of an expiring patriotism.” Both Washington and Adams assumed that unless the United States and France scored a decisive victory in 1781, the outcome of the war would be determined at a conference of Europe’s great powers.

Stalemated wars often conclude with belligerents retaining what they possessed at the moment an armistice is reached. Had the outcome been determined by a European peace conference, Britain would likely have retained Canada, the trans-Appalachian West, part of present-day Maine, New York City and Long Island, Georgia and much of South Carolina, Florida (acquired from Spain in a previous war) and several Caribbean islands. To keep this great empire, which would have encircled the tiny United States, Britain had only to avoid decisive losses in 1781.

Yet Cornwallis’ stunning defeat at Yorktown in October cost Britain everything but Canada.

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ratified the American victory and recognized the existence of the new United States. General Washington, addressing a gathering of soldiers at West Point, told the men that they had secured America’s “independence and sovereignty.”

The new nation, he said, faced “enlarged prospects of happiness,” adding that all free Americans could enjoy “personal independence.” The passage of time would demonstrate that Washington, far from creating yet another myth surrounding the outcome of the war, had voiced the real promise of the new nation.

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

EURO-WAR / HOW JOE GAVE D.C. THE SLIP

GUEST BLOG / By the Zeke Miller, Associated Press aboard Biden's low key modified Boeing 757 to Ukraine--President Joe Biden’s motorcade slipped out of the White House around 3:30 a.m. Sunday. No big, flashy Air Force One for this trip -– the president vanished into the darkness on an Air Force C-32, a modified Boeing 757 normally used for domestic trips to smaller airports.

The next time he turned up — 20 hours later — it was in downtown Kyiv, Ukraine.

Biden’s surprise 23-hour visit to Ukraine on Monday was the first time in modern history that a U.S. leader visited a warzone outside the aegis of the U.S. military — a feat the White House said carried some risk even though Moscow was given a heads-up.

|

| Presidents of the Ukraine and the United States of America |

Over the next five hours, the president made multiple stops around town — ferried about in a white SUV rather than the presidential limousine — without any announcement to the Ukrainian public that he was there. But all that activity attracted enough attention that word of his presence leaked out well before he could get back to Poland, which was the original plan. Aides at the White House were surprised the secret held as long as it did.

But Russia knew what the Ukrainian public did not. U.S. officials had given Moscow notice of Biden’s trip.

The president had been itching since last year to join the parade of other Western officials who have visited Kyiv to pledge support standing shoulder to shoulder with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in the capital.

Biden’s planned trip to Warsaw, Poland, and the Presidents’ Day holiday provided an obvious opening to tack on a stop in Kyiv. A small group of senior officials at the White House and across U.S. national security agencies set about working in secret for months to make it happen, national security adviser Jake Sullivan said Monday. Biden only gave the final sign-off Friday.

Sullivan said the trip “required a security, operational, and logistical effort from professionals across the U.S. government to take what was an inherently risky undertaking and make it a manageable risk.”

Once Biden was secreted aboard the Air Force jet, the call sign “SAM060,” for Special Air Mission, was used for the plane instead of the usual “Air Force One.” It was parked in the dark with the window-shades down, and took off from Joint Base Andrews at 4:15 a.m. Eastern time.

After a refueling stop in Germany, where the president was kept aboard the aircraft, Biden’s plane switched off its transponder for the roughly hour-long flight to Rzeszow, Poland, the airport that has served as the gateway for billions of dollars in Western arms and VIP visitors into Ukraine. From there, he boarded a train for the roughly 10-hour overnight trip to Kyiv.

He arrived in the capital at 8 a.m. Monday, was greeted by Ambassador Bridget Brink and entered his motorcade for the drive to Mariinsky Palace. Even while he was on the ground in Ukraine, flights transporting military equipment and other goods were continuing unabated to Rzeszow from Western cities.

Meanwhile, in Kyiv, many main streets and central blocks were cordoned off without explanation. People started sharing videos of long motorcades of cars speeding along streets where access was restricted — the first clues that Biden had arrived.

Biden traveled with a far smaller than usual retinue: Sullivan, deputy chief of staff Jen O’Malley Dillon and the director of Oval Office operations, Annie Tomasini. They were joined by his Secret Service detail, the military aide carrying the so-called “nuclear football,” a small medical team and the official White House photographer.

Only two journalists were on board instead of the usual complement of 13. Their electronic devices were powered off and turned over to the White House for the duration of the trip into Ukraine. A small number of journalists based in Ukraine were summoned to a downtown hotel on Monday morning to join them, not informed that Biden was visiting until shortly before his arrival.

Even with Western surface-to-air missile systems bolstering Ukraine’s defenses, it was rare for a U.S. leader to travel to a conflict zone where the U.S. or its allies did not have control over the airspace.

The U.S. military does not have a presence in Ukraine other than a small detachment of Marines guarding the embassy in Kyiv, making Biden’s visit more complicated than visits by prior U.S. leaders to war zones.

“We did notify the Russians that President Biden will be traveling to Kyiv,” Sullivan told reporters. “We did so some hours before his departure for deconfliction purposes.” He declined to specify the exact message or to whom it was delivered but said the heads-up was to avoid any miscalculation that could bring the two nuclear-armed nations into direct conflict.

While Biden was in Kyiv, U.S. surveillance planes, including E-3 Sentry airborne radar and an electronic RC-135W Rivet Joint aircraft, were keeping watch over Kyiv from Polish airspace.

The sealing off of Kyiv roads that are usually humming with traffic brought an eerie calm to the center of the capital. It was so quiet that crows could be heard cawing as Biden and Zelenskyy walked from their motorcade to the gold-domed St. Michael’s Cathedral under skies as blue as the outer walls of the cathedral itself.

“Let’s walk in and take a look,” Biden said, wearing his trademark aviator sunglasses against the glare. The presidents disappeared inside as heavily armed soldiers stood guard outside.

Cathedral bells chirped at the stroke of 11:30 a.m. followed shortly by air raid alarms, at 11:34 a.m., just before the men reemerged. The sirens were first a distant howl rising over the city, followed seconds later by alarms from mobile phone apps wailing from people’s pockets.

Those alarms are voiced by “Star Wars” actor Mark Hamill, and his Luke Skywalker voice urged people to take cover, warning: “Don’t be careless. Your overconfidence is your weakness.”

The two leaders walked at a measured pace with no outward signs of concern through the cathedral’s arched front gate onto the square in front, where the rusting hulks of destroyed Russian tanks and other armored vehicles have been stationed as grim reminders of the war.

When the square isn’t blocked off, as it was during the leaders’ visit, people come to look at the vehicles, many taking selfies.

Biden appeared to pay the hulks no mind as he and Zelenskyy followed behind honor guards carrying two wreaths to the wall of remembrance honoring Ukrainian soldiers killed since 2014, the year Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula and Russian-backed fighting erupted in eastern Ukraine.

It was only then that the first images of Biden in the capital popped up on Ukrainian social media and the secret visit became global news.

“He is like an example of a president who is not afraid to show up in Ukraine and to support us,” said Kyiv resident Myroslava Renova, 23, after Biden’s visit became known.

Biden headed to the U.S. Embassy for a brief stop before departing the country by train back to Poland aboard a well-appointed, wood-paneled train car with tightly drawn curtains, a dining table and a leather sofa.The all-clear notice, also voiced by Hamill, sounded at 1:07 p.m., as Biden’s train was pulling away from the station. “The air alert is over,” Hamill said. “May the force be with you.”

___

Associated Press photographer Evan Vucci reported from aboard Biden’s aircraft and in Kyiv. Miller reported from Washington. Associated Press writers Aamer Madhani in Washington and Nicolae Dumitrache in Kyiv contributed.

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

PRESIDENT’S DAY ESSAY / LINCOLN’S “MIRACLE” NOMINATION IN 1860

How One Week in Chicago Changed Abraham Lincoln’s Life—and the Fate of the United States

In focusing on the steps that led to a result, we can’t help but form the impression that the outcome was inevitable. We forget that the people in the middle of the most momentous events in our history had no idea what would happen.

That is why I like suspending the usual viewpoint of history from 30,000 feet up and taking events down to ground level.

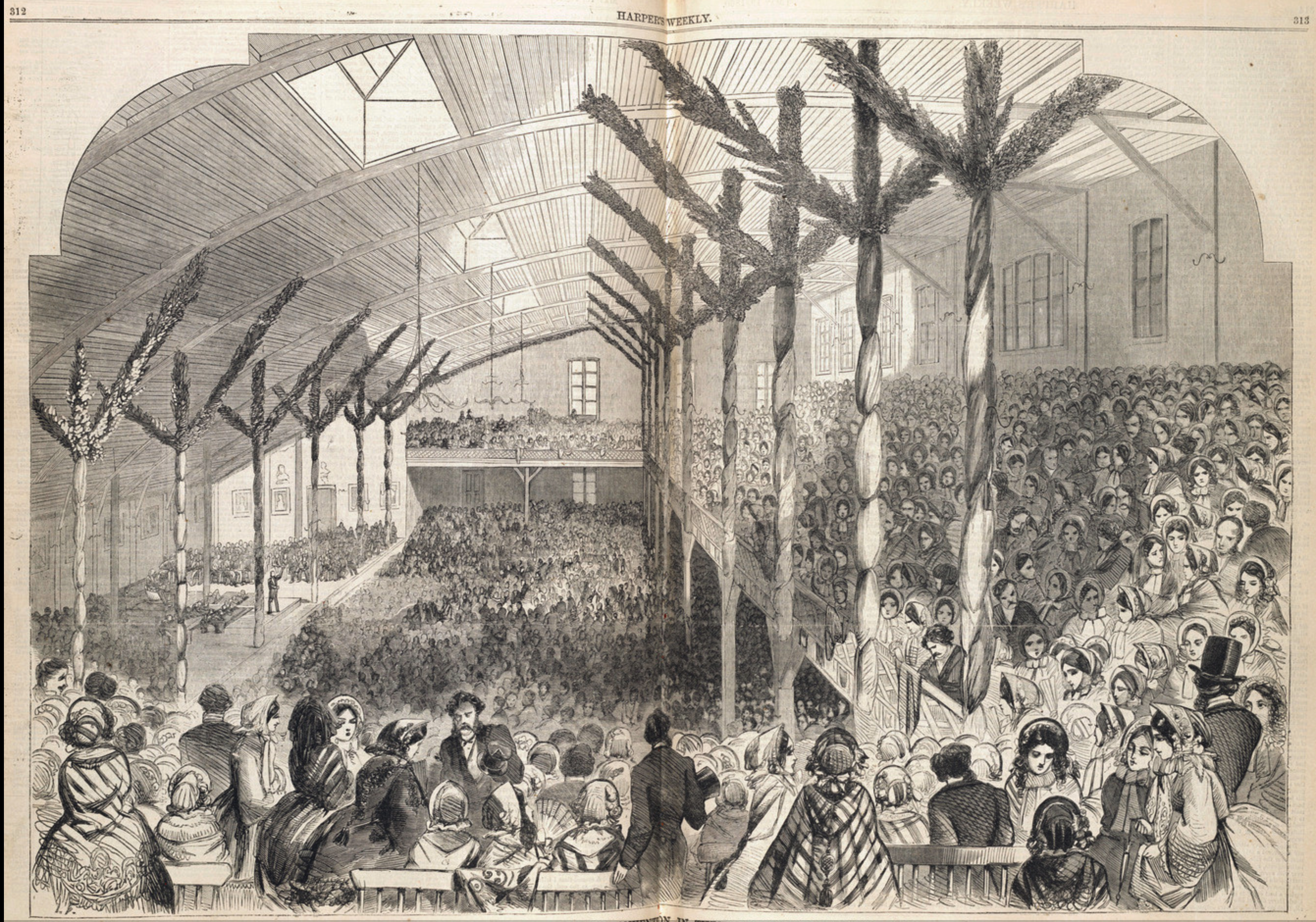

In my latest book, The Lincoln Miracle: Inside the Republican Convention That Changed History, that means the floor of the Wigwam, a freshly built, massive auditorium of fragrant, unfinished wood, and in the crowded, smoky, tobacco-juice-stained saloons and hotel rooms of Chicago during one week in May 1860.We find there a story unfolding so astonishing—and so crucial to the ultimate survival of the United States, and the destruction of slavery—that some who were there thought the invisible hand of the Almighty shaped the outcome.

I consider what happened that week a miracle.

Given Abraham Lincoln’s stature—he regularly tops lists of the greatest US presidents—his rise to prominence seems a foregone conclusion. But it was anything but.

This is the week that propelled him to greatness. Without his subsequent role as president, no one would have meticulously recorded his life’s story. As historian Mark E. Neely Jr. wrote, “Had Abraham Lincoln died in the spring of 1860, on the eve of his first presidential nomination, he would be a forgotten man.”

We may not appreciate what a long shot Lincoln was going into the convention that nominated him. The resumes of other candidates towered over his own. He had grown up poor and had next to no formal education. He told vulgar—at times, dirty—jokes. He had not held elected office for more than a decade. His one two-year term in Congress had been regarded by many as a failure. He had lost two campaigns for the Senate. His executive experience was pretty much limited to running a two-man law office.

“Just think of such a sucker as me as President!” Lincoln himself had told people he did not think himself fit for the presidency, and two years earlier he declared, with roaring laughter, “Just think of such a sucker as me as President!”

Even while lining up support, Lincoln did not formally declare his presidency. He told a close ally: “The taste is in my mouth a little.” In fact, Lincoln’s chances seemed so remote that the leaders of the Republican National Committee approved Chicago as the convention site in part because they thought it was neutral ground. No major candidate, they concluded, hailed from Illinois.

In a lithograph centerspread of the candidates published on Saturday, May 12, 1860, Harper’s Weekly played Lincoln’s picture on the bottom with the also-rans; its written description of Lincoln was dead last among all the candidates. At best, people were talking about Lincoln as a possible vice-presidential nominee, coming as he did from an important swing state.

From Harper’s Weekly, May 12, 1860. Front and center, with the biggest picture and first and longest write-up, was the superstar of the Republican party, the former governor of New York and current US Senator William Seward. Seward was regarded as the founder and father of the Republican Party, a bold opponent of slavery and defender of the rights of immigrants, and he was managed by a brilliant political strategist named Thurlow Weed, who could make or break senators and presidents.

He had more money behind him than any candidate. Under our modern system, he would have rolled through the primaries. Lincoln wouldn’t have had a prayer. But in 1860, Seward’s strength was deceptive. The previous October, abolitionist John Brown had raided a federal armory and planned to provide enslaved people with guns for a violent insurrection against whites. While Brown was apprehended and hanged, the incident infuriated the South and terrified many voters in the North.

Many thought all this slavery talk was putting impossible pressures on the political system and threatening to break the nation in two, igniting a bloody civil war. And nobody was more famous for anti-slavery rhetoric than William Seward. Party leaders worried about that. Though Lincoln had made many of the same points against slavery, he was far less known to the voters—thus, less scary.

Today’s readers will no doubt find a haunting familiarity in the mood of 1860. Politics seemed to have broken down. Those who disagreed could no longer discuss issues. On top of that Seward had openly supported immigrants and was close to Catholic leaders, something that turned off a sizable portion of the Republican base, who feared that rampant immigration was helping Democrats steal elections and destroying America from within.

Former members of the American Party, often called the Know-Nothing Party, might well bolt from the Republicans if they nominated Seward. Lincoln’s position on immigrants, meanwhile, was so little known that some people assumed he was a Know-Nothing. (In truth, Lincoln despised the movement.)

Today’s readers will no doubt find a haunting familiarity in the mood of 1860. Politics seemed to have broken down. Those who disagreed could no longer discuss issues; they talked past each other and increasingly looked to violence to get their way. One major party suffered bitter internal divisions.

Even the selection of a House speaker, normally a rote affair, dragged on. Many viewed Washington as a festering swamp of corruption run by elites who had lost contact with the common people. One of the most striking things that quickly became clear in my research was that these men gathered in Chicago were not choosing a candidate on the basis of who might make the best president in that climate of crisis.

Their biggest concern, by far, was who would get the most Republicans elected, which meant power, jobs, and money. The pro-Lincoln Chicago Press and Tribune appealed to this naked self-interest in an editorial aimed at arriving delegates: “Constables are worth more than Presidents in the long run, as a means of holding political power. … We look to Mr. Lincoln to tow constables and General Assembly [members] into power … The gods help those who help themselves.”

There was something else going for Lincoln that wasn’t immediately apparent to the national press. Though he was a minor figure nationally and had been defeated repeatedly, he had built an intensely loyal following in Illinois. With home-field advantage, they made an enormous difference in Chicago.

Early in the convention, the “moderate” alternative to Seward appeared to be a Missouri judge named Edward Bates. His supporters argued he would calm the South and negate all threats of succession, and he had the backing of some powerful forces—notably, the most influential newspaper editor in the country, Horace Greeley, who came to Chicago to undermine Seward for blocking his political career.

Unfortunately for Bates, German immigrants were dead set against him, because he had flirted with the Know-Nothing Party. Prominent Germans went so far as to hold their own national convention that same week just down the road from the Republican one, sending a terrifying signal to the delegates.

Though German immigrants made up only a small percentage of Republican voters, that was enough to sway elections in many Northern states. The delegates did not dare go with Bates.

I called my book The Lincoln Miracle in part because so many things beyond Lincoln’s control slotted into place perfectly to advance him. There are too many to recite in this short essay that I recount in the book.

Some events that week seem almost spookily fortuitous. On Thursday, May 17, Seward had won a series of test votes and seemed poised to win the nomination. But tally sheets had not arrived at the rostrum. Rather than wait just a few minutes, hungry delegates adjourned for the day—leaving the Lincoln men the opportunity to work all night cutting deals.

On such slender threads hang the fate of nations. They also evidently forged counterfeit tickets to the convention hall. When Seward supporters arrived at the Wigwam after marching in the streets the next morning, they found Lincoln men occupying their seats—giving delegates an oversized impression of the support in the hall for Lincoln during the voting for president.

The greatest miracle, of course, was the nature of the man nominated. Delegates knew Lincoln as a strong speaker and a loyal Republican. But they could have had no idea of his strengths of stubborn willpower, subtlety of mind, literary genius, and political brilliance. Lincoln was arguably the only one of the candidates who could have saved the nation in its time of greatest peril and ended the moral abomination of chattel slavery.

For that reason, one journalist covering the convention later argued that the men at the Wigwam were “the unconscious instruments of a Higher Power.” I hope you join me on the wild ride of that week to experience how great a miracle Abraham Lincoln was. -- Reposted from Literary Hub, February 16, 2023 [LitHub.com].

CLICK HERE TO PURCHASE FROM GROVE ATLANTIC

Monday, February 20, 2023

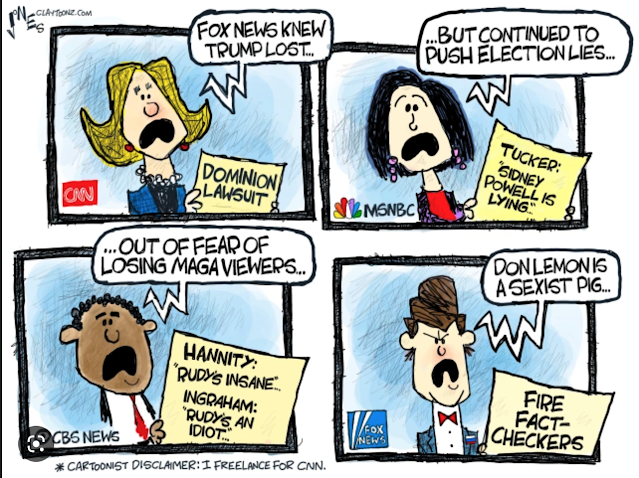

MEDIA MONDAY / POST 2020 ELECTION FEARS SHOW UP IN LAWSUIT

CLICK HERE so as not to miss a remarkable work of journalism by the Associated Press national media writer David Bauder.

Here’s a tease:

NEW YORK (AP) — A court filing in a lawsuit against Fox News lays bare a panic at the network that it had alienated its viewers and damaged its brand by not lining up with President Donald Trump’s false claims that he had won the 2020 presidential election. That worry — a real one, judging by Fox’s ratings in the election’s

|

| AP's David Bauder |

|

| Cartoon by Ann Telnaes, Washington Post |

Sunday, February 19, 2023

SUNDAY REVIEW / BOOK/COFFEE SHOP HAPPENSTANCE ROMANCE

|

| Libelula Books, Barrio Logan, San Diego, CA |

I'm inspired by how dragonflies are both tough and fragile; fierce and mild.”

― Cindy Crosby, Author of "Chasing Dragonflies: A Natural, Cultural, and Personal History."

GUEST BLOG / By Jesi Gutiérrez & Celi Hernández, published in the community section of the San Diego Union Tribune-- If you would’ve told us 10 years ago that six days a week, every evening at 5:59 p.m., we would be turning off small funky lamps sprinkled throughout colorful bookshelves, stacking a book cart and scooping up the world’s cutest cat to take home after a full day at the bookshop we co-own in Barrio Logan, we would have both bet money to prove the impossibility.

|

| Celi Hernandez |

On weekends, it was crawling with tourists who flocked to Seaport Village to capture the picturesque waterfront and buy overpriced silly socks. But Monday through Thursday? Those four long, sun-filled days belonged to the locals, the seagulls and the kites. And to us. As we remember it, one particular Monday was the slowest of slow days. The perfect day for Celi to walk into an old, cozy bookshop, order a coffee and make herself comfortable upstairs with a stack of books and a cup of coffee.

|

| Jesi Gutierrez |

You see, the barista had had a longtime quiet crush on this Monday reader and part-time hat milliner. Armored in a work apron, the barista prepared a curious assortment of cookies, a favorite book — “All About Love: New Visions” by bell hooks — and a refill cup of coffee. Tray in hand, the barista made the long journey up the stairs and, without breathing, asked to sit at the milliner’s table.

Ten years later, and we are still making bets on one another and trying to decide how we can fit more bookish fun and art into Libélula’s small 700-square-foot space. Gutiérrez and Hernández are co-owners of Libélula Books & Co. in Barrio Logan neighborhood where they live.

Saturday, February 18, 2023

COFFEE BEANS & BEINGS / MEET TOM, THE ROBOT BARISTA & OTHERS.

Tom, the Tokyo Barista

GUEST BLOG / By Chris Albrecht, The Spoon--Growing up, UHF TV stations would run Japanese anime cartoons that featured giant robots. Fast forward a few decades to when I finally got the chance to visit Tokyo, and I thought the city would be lousy with robots.

But sadly, that turned out not to be the case. In fact, I could only find one coffee robot in Tokyo — which is a bit surprising, given that San Francisco area has almost a dozen, plus another one at SFO airport.

Nestled in the heart of the H.I.S. travel agency in the Shibuya part of Tokyo sits the Henn Na Cafe (fun fact, Henn Na means weird in Japanese). “Tom,” the autonomous articulating arm that serves up hot and iced coffee, matcha tea and other assorted drinks and snacks.

Tom is akin to Cafe X (San Fran), but doesn’t offer the same variety, and, at least from my viewing, sadly doesn’t perform any theatrics for customers. Tom does, however, sport a pair of bright eyes and a dapper chapeau for a more personal touch.

Tom and the Henn Na Cafe were installed in H.I.S. in February of last year because the travel agency thought that as people plan their vacations, they would like to discuss them in a cafe-like setting. But it wasn’t feasible for the company to dedicate staff to making lattes, so it brought Tom online.

Tom is actually two robots: the articulating arm, which shuttles cups and coffee grounds around, and the PourSteady, an automated pour-over coffee machine. Place an order for hot or iced coffee at the nearby kiosk and Tom whirrs into action. Three to four minutes later, Tom pulls your finished coffee and sets it in a small case for people to pick up.

Though unlike other coffee robots, this is just a plain case with no screen or anything to indicate whose drink is up. But that probably isn’t as necessary, given H.I.S. is a travel agency first, and the cafe is more of a, pardon the pun, perk.

OTHER ROBOT BARISTAS

|

| San Francisco: SFO Airport: Open 24/7 near gate B20, Terminal 1, operated by Café X. |

|

| Pleasanton CA: Artly Coffee Kiosk at Stoneridge Shopping Center. |

Friday, February 17, 2023

FRIDAY FLOODS / MISSION BEACH BOARDWALK FLOODED

ICYMI. A storm brought to San Diego by an atmospheric river has moved out of the region, allowing sunny skies to return to San Diego, but the county is still feeling the storm's effects in the form of high surf, flooding and road damage. In Mission Beach, San Diego lifeguards were also prepared for flooding of the boardwalk and other areas around the Bay. The channel to Mission Bay was closed Friday morning as knocking waves crashed against the jetties. Video sent in from MissionBeach.SD shows waves crashing over the boardwalk and making it to houses nearby.

Last time a storm and high tides flooded Mission Beach was the winter of 1983.

Thursday, February 16, 2023

THE FOODIST /TOMATOMANIA EXCITEMENT COMING TO SAN DIEGO AREA

SAVE THE DATES

February 24th and 25th, El Cajon, The Water Conservation Garden; Located at Cuyamaca College, 12122 Cuyamaca College Drive West, 9 am to 4 pm.

February 25th and 26th, San Diego, Mission Hills Nursery, 1525 Fort Stockton, Drive, San Diego, 8 am to 5 pm.

Tomatomania staff will join two San Diego area nursery groups to introduce you to over 125 varieties of unique and exciting tomatoes.

They will also introduce you to our 2023 Tomato of the Year, Melanie’s Ballet, (a dwarf standout last season!) and other wonderful new heirloom dwarf plants that will be perfect for your containers and raised beds.

Cages, containers, fertilizers, soils and everything you’ll need for your season will all be available.

Early, is a key word here and often the tomato is the first plant to produce fruit in June. Tomatomania producer Scott Daigre says this about the 2023 choice: “The extraordinary thing about this variety is not stripes or lobes or immense size. It’s just a dependable and tasty character in the garden. It produces well early in the season on a plant that seems to thrive and fruit well with minimum effort. It will make many a home gardener feel like a very successful farmer. I like the value in that."

You will have the chance to review the seedling collections, along with fulfilling all of your gardening needs at Tomatomania events all across the Southland. The full schedule can be found at Tomatomania.com

About Tomatomania!

Each Tomatomania event is unique, with the largest and longest running California seedling sale, welcoming thousands of tomato lovers to an annual tomato extravaganza showcasing more than 300 heirloom and hybrid tomato varieties.

Featuring everything from pots and fertilizer to stakes and enthusiastic expert advice, their events are the one-stop shop for growing great-tasting tomatoes in your own backyard.

Leading the team of tomatomaniacs is Scott Daigre, owner of Powerplant Garden Design based in Ojai, California. He has been running Tomatomania for more than 20 years. Scott is the author of the best-selling book “Tomatomania: A Fresh Approach to Celebrating Tomatoes in the Garden” A dedicated home gardener, Scott shares his love of digging in the dirt through event appearances, speaking engagements, books, and videos that offer tools and tips for amateur and veteran gardeners alike. |

| El Cajon, The Water Conservation Garden |

|

| San Diego, Mission Hills Nursery |

.jpg)