|

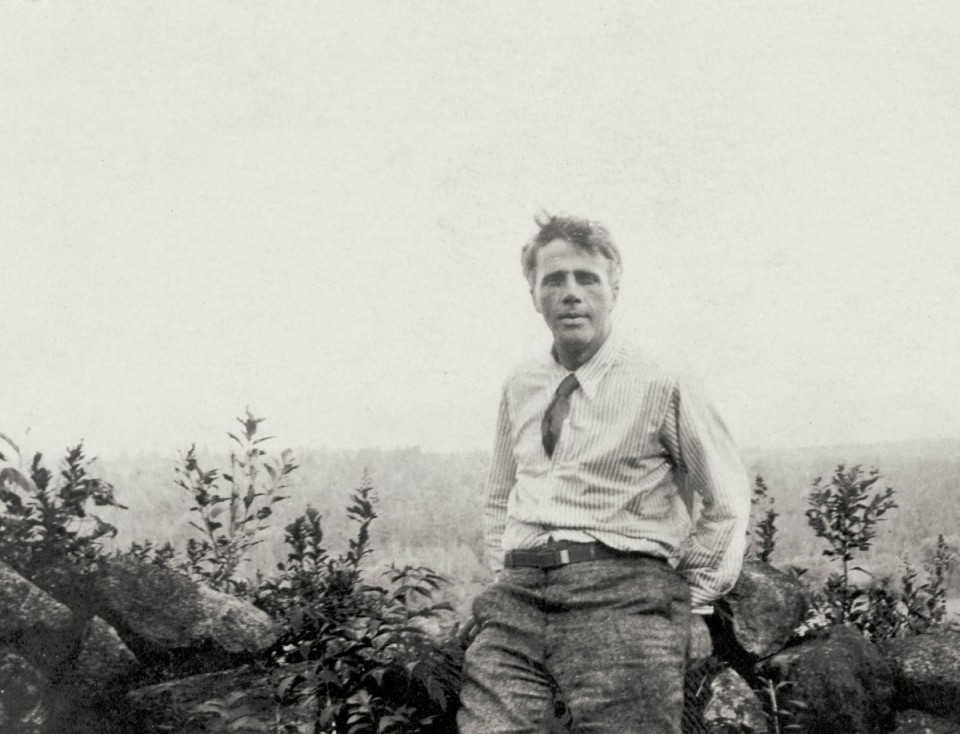

| Robert Frost (The New Yorker) |

GUEST BLOG / By Mike Pride, editor emeritus of the Concord Monitor and retired administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes--“When I retired as editor of the Concord Monitor a decade ago, the publisher gave me a gift I still treasure. It is a first edition of "New Hampshire," Robert Frost’s 1923 poetry collection. The long title poem is full of wry observations about the state, but if it is remembered at all, it is for a snooty quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “The God who made New Hampshire / Taunted the lofty land with little men.”

Folded inside the back cover of the book was a contemporary review of New Hampshire by someone with the initials D.T.C. McC. After reading the review, I researched the writer. When I didn’t find the review on the internet, I decided to write a column including the entire review, thus rescuing it from obscurity.

“D.T.W. McC.” turned out to be David Thomas Watson McCord, who was just shy of his 26th birthday when the Boston Evening Transcript published the review on Dec. 8, 1923. He had been in the Harvard class of 1921 and earned his master’s in chemistry there the following year. For 38 years he was executive director of the Harvard Fund, retiring in 1963.

McCord’s obituary — he died in 1997 at the age of 99 — recounted that after living in Princeton, N.J., as a boy, he moved to Oregon at age 12 to live on a remote farm with his uncle. It was there, on the edge of the wilderness, that he began to learn to write. “Poetry is rhythm,” he observed of that time, “just as the planet Earth is rhythm; the best writing, poetry or prose — no matter what the message it conveys — depends on a very sure and subtle rhythm.”

In 1956, Harvard celebrated his achievements with its first honorary degree of doctor of humane letters.

THE FOLLOWING: Here is McCord’s 1923 review of Frost’s "New Hampshire":

It becomes more and more apparent that Robert Frost is New England’s most authentic poet, and by authentic poet we mean the most sincere, foursquare and forthright who has tried to lay a finger on the slow and positive pulse of the New England north of Boston and sound the secret of its heart.

He is of the hills of New Hampshire — “Taunted,” perhaps, as Emerson says, “with little men,” and he knows them as well as Yeats knows Ireland or Swinburne knew the North Sea; and as for the “little men,” he can speak quite well, for he knows them too.

“I called the fireman with a careful voice and bade him leave the pan and stoke the arch,” he wrote in a sonnet (from New Hampshire) all about Spring and a sugar orchard; and here we discover four words which are something of a touchstone to the bulk of his poetry. “With a careful voice” — that indeed is Robert Frost, careful in execution, careful in diction, careful, sometimes to the point of tediousness, in the detail of a picture.

To this matter of care and quiet plodding Mr. Frost owes much of his success. One can hardly believe him capable of very strong emotion, yet he has recollected much of it — and that in the darkest of tranquility. His poetry has evolved slowly, each creation measured with the practiced eye that goes afield in search of just the right stone for the chimney corner, and one fancies him polishing and re-polishing, but never to brilliance, with the patience of Malherbe (French poet, 1555-1628). In his creative mood we may think of him as leaning across a stone wall in the hush of a summer afternoon and talking intimate-fashion:

You know Orion always comes up sideways,

Throwing a leg up over our fence of mountains,

And rising on his hands, he looks in on me

Busy outdoors by lantern-light with something

I should have done by daylight, and indeed,

After the ground is frozen, I should have done

Before it froze, and a gust flings a handful

Of waste leaves at my smoky lantern chimney

To make fun of my way of doing things,

Or else fun of Orion for having caught me . . . (from “The Star Splitter”)

With this preamble we come to Mr. Frost’s new book, "New Hampshire, a Poem with Notes and Grace Notes," illustrated with three splendid wood engravings by J.J. Lankes.

Perhaps the subtitle is misleading. The “notes” are nothing less than poems of moderate length, each fastening a vital tendril upon individual lines or parts of the central poem, and the “grace notes,” which will be the first read and the most admired, are brief lyrics, small shatter fragments of clear beauty, the not too remote supplements of their larger-bodied brothers.

There is a great homogeneity to it all — New Hampshire, “one of the two best States in the Union. Vermont’s the other”; New Hampshire, that possesses, or once possessed, a specimen of everything: a Daniel Webster, a bit of gold, a trace of radium, a reformer, a witch, but not much of anything in commercial quantities except poems; New Hampshire, where the level of intelligence is such that a Warren farmer, come suddenly upon you, may say ten words about Bryant and mid-Victorians. Here is what outsiders think of it, there is what the poet thinks of it; now some meditation on a fallen meteorite, an estimate of the farmyard grindstone, a delineation of two witches, a pathetic poem about a deserted house and a box of books, and so on.

Homogeneity, yes. But can all such stuff be part and parcel of poetry? Indeed it can. Mr. Frost has set his main theme in the blank verse which he fashions so adroitly. He has packed it with thought, both sober and witty, with homely imagery and the rich flavor of White Mountain speech, and made it to wind along like a rough and pleasant path among the hills.

It has been said that Mr. Frost apparently polishes his work, but never to brilliance. When one reads the pages of his new book, finding such glorious titles as “A Star in a Stone-Boat,” “Our Singing Strength” or “The Star Splitter,” one may easily expect the pinion sweep of Mr. (Edward Arlington) Robinson. To do that is to be disappointed. Mr. Frost sails on an even keel, and his polishing has gone to make fruitless the simplicity and naturalness of the lines, not to give them the ethereal quality one may see with Mr. Robinson in “The Man against the Sky,” but with almost everything that Robert Frost has done one shuffles through the autumn leaves upon a lonely road — and enjoys it immensely.

Mr. Frost has ideas and originality, both of which are most apparent in New Hampshire. His greatest defect is too much sameness of form. In all of the longer pieces there is the swing of blank verse, and often twenty lines of a poem may be read before one is aware of rhyme; a fact, however, wholly untrue of the grace notes. His method of relief is humor:

And weren’t there special cemetery flowers,

That, once grief sets to growing, grief may rest: The flowers will go on with grief awhile, And no one seem neglecting or neglected. A good deal of a philosopher, Mr. Frost digs down into the heart of New Hampshire life and deracinates with extreme cleverness and subtlety its changing aspects. Yet his old loves have not been lost, and those who turn to a new volume of (John) Masefield for the salt water ballad that may be there will find here another “swinging birch” poem and much that is akin to “Mending Wall.” -- D.T.W. McC.

No comments:

Post a Comment