From the preface of the House Committee on Ways and Means report on the IRS’s mandatory tax audit program.

GUEST BLOG / By Congressional Chair of Ways and Means Committee Richard E. Neal--At the opening of every Congress, each person undertaking office as a member of the United States House of Representatives or the United States Senate swears to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” Our civil servants and members of the armed forces pledge to do the same. The President of the United States must likewise swear that he or she “will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Unlike the custom in many other parts of the world, none of these officials owes any oath of loyalty to a king, a queen, an autocrat, or a political party.

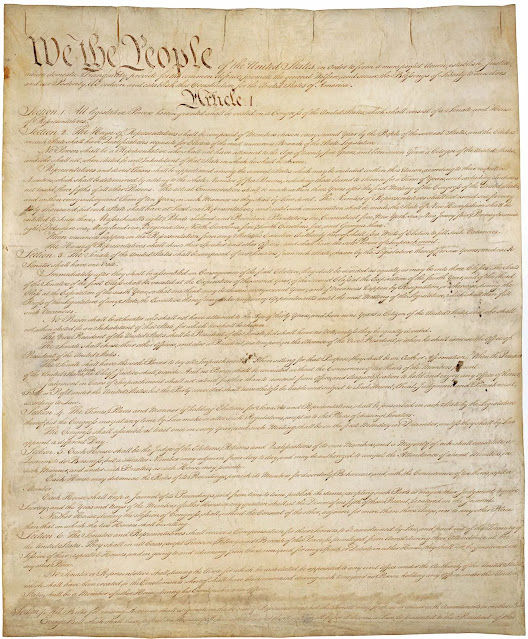

The roots of this practice we observe today stretch back to our country’s earliest days. When the United States was founded, vesting a nation’s ultimate power and legal authority in a constitution—instead of in an individual—was a radical concept and a highly deliberate decision. The Framers understood this choice very well: they had been subjects of King George, who wielded power cruelly and arbitrarily. All around them, they had seen the consequences of unconstrained power preserved in the hands of an unaccountable leader who held himself above the law.

The people were answerable to laws that they had no part in approving. They were required to pay heavy taxes and to quarter British soldiers in their homes against their will. They were subject to trials with no right to a jury. The justice system was misnamed: judges were selected and paid by the King—and expected to do his bidding. The host of insults to their autonomy and the miscarriages of justice mounted so high that eventually, the colonists saw no alternative but to wage a war of independence.

When they won it and took on the task of organizing a new government, they were determined not to trade one autocrat for another. They negotiated a constitution that constrained power by distributing governmental authority across three separate and independent branches and establishing robust checks and balances among them. They required elections for many offices, with terms that expired after a specified period. They ensured that those who would hold office would be subject to public accountability through impeachment processes. They aimed to make their people citizens and not subjects, and their leaders representatives and not tyrants.

While to this day an imperfect document, the U.S. Constitution was and remains a groundbreaking experiment in democracy.

This experiment, and these institutions, survive not because they are inevitable: they are not. They survive because we value and defend them. The Framers enshrined in our constitution a kernel of truth from the first tentative spark of the Magna Carta in 1215: that we consent to a rule of law, not a law of rulers. In the United States of America, no one is above the law, even— perhaps especially—the President.

Just like every other American, the President of the United States is obligated to pay taxes owed. This is a core responsibility of our common citizenship: without tax revenue, our government would cease to exist. Unlike many nations, we operate a largely voluntary tax compliance system, supported by oversight and auditing. That means that our revenue system— and hence our democracy—hinge on public faith that our tax laws are administered fairly and without favor.

Auditing the income taxes of the President of the United States is unlike auditing the income taxes of any other American. No one else has the power to sign bills into law—bills that could affect the President’s personal financial situation. Nor do they have the power to personally direct every department, agency, bureau, and office of the vast executive branch of government— opening limitless opportunities to affect the President’s personal finances. And no other American has the comparable power to appoint or terminate officials responsible for decisions that could affect the President’s personal financial prospects.

We maintain that how Presidents exercise these powers and the extent to which the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits and enforces our federal tax laws to ensure compliance by Presidents, are a valid and crucial subject of legislative scrutiny. The public must have confidence that our tax laws apply evenly and justly to all, regardless of power or position. The effort to provide oversight of the mandatory audit program is and always has been about ensuring that our tax laws are administered fairly and without preference.

The Committee’s investigation revealed only one mandatory audit was started under the prior Administration and the program was otherwise dormant, at best. For this reason, it is recommended that there should be a statutory requirement for the mandatory examination of the President with disclosure of certain audit information and related returns in a timely manner. Such statutory requirements would ensure the integrity of the IRS, enable IRS employees to fully audit all issues, and restore confidence in the Federal tax system.

No comments:

Post a Comment